As French humorist Pierre Desproges remarked, “You can laugh at everything, but not with everyone.” What people find funny is far from universal, making humor a challenging terrain to navigate on a global scale.

Case in point: In a 2011 interview, Australian TV show host Karl Stefanovic attempted to share a joke with the Dalai Lama. “So, the Dalai Lama walks into a pizza shop,” he quipped, “and says, can you make me one with everything?” “Huh,” responded his Holiness with a perplexed expression, and turned to his aides, “What’s that?” The pun, connecting spiritual unity and a pizza with everything, was utterly lost on the non-native speaker of English.

To remedy this awkward situation and achieve a comical effect similar to its English version, translators would have had to engineer the joke from scratch in Tibetan, his native tongue. This is because puns translated verbatim are almost always lost in the target language. This act of localization by transcreation is not only useful in interviews with the Dalai Lama, it is also vital for international business, given that 68% of people prefer an end-to-end customer experience in their own language.

Humor is much more than a cosmetic veneer. It is a fantastic way to create rapport with people and build trust.

In Humor, Seriously: Why Humor Is a Secret Weapon in Business and Life, behavioral scientists Jennifer Aeker and Naomi Bagdonas argue that “humor has a profound impact on human psychology and behavior […] This emerging field just might become one of the greatest competitive advantages in business.” Their list of what humor can do includes: connecting people on a fundamental and emotional level; making a point about deeper meaning without being too on the nose; increasing the long-term retention of the message; fostering a sense of psychological safety and a belief in the intelligence of the joker; accelerating the path to trust; unlocking creativity, and increasing product/brand loyalty. It does all this through a complex neurochemical process, where the brain releases a cocktail of hormones making us feel “happier (dopamine), more trusting (oxytocin), less stressed (lowered cortisol), and even slightly euphoric (endorphins).”

This only works, of course, if the joke hits the audience on an emotional level and makes them laugh. Successful humor is ultimately grounded in the sensibilities, references and associations specific to a particular community. They need to make sense (a) linguistically and (b) culturally—and it is precisely here, where translations of humor usually fail.

Defining failure: Linguistic vs cultural mistakes

The example with the Dalai Lama falls into the first category of “linguistic failures,” which has more to do with the form of the message than its content. In Is That a Fish in Your Ear? Translation and the Meaning of Everything, David Bellos refers to them as metalinguistic expressions, “sentences and phrases that refer to some aspect of their own linguistic form—carry meanings that are by definition internal to the language in which they are couched.” As a result, it is impossible to translate them directly into another language and also preserve the joke.

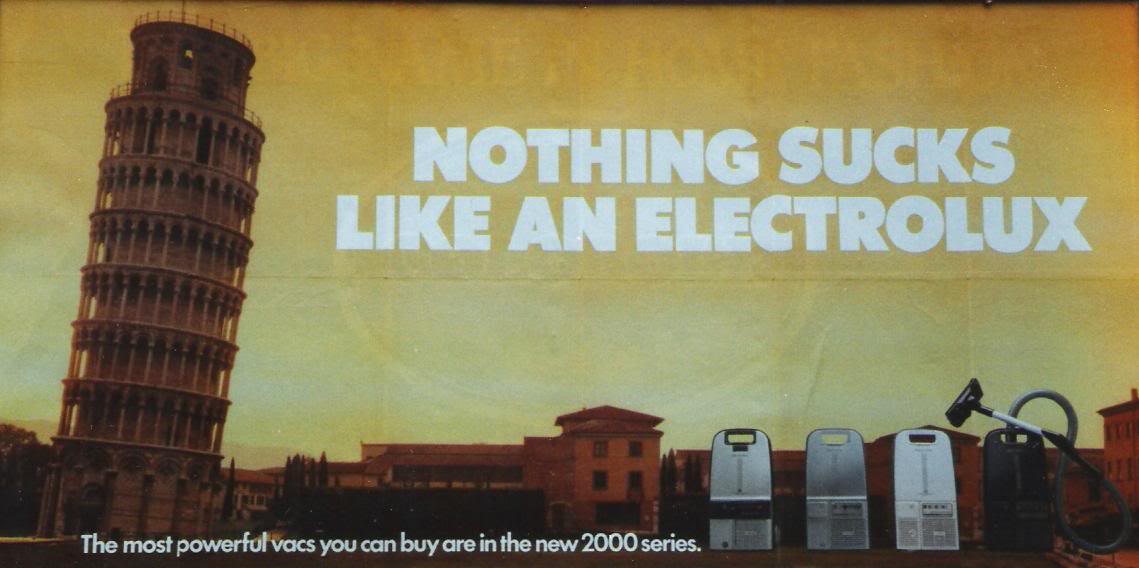

As a side note, translation failures sometimes create humor when none is intended in the original. Two examples of this in the Anglo-American market are the Ikea Fartfull workbench (“speedy” in Swedish, a reference to the piece of furniture being on wheels) and “Nothing sucks like an Electrolux” (the company’s unfortunate attempt to market their vacuum cleaner in the English-speaking market during the 70s).

While the campaign’s intention was innocent, the slogan “Nothing sucks like an Electrolux” was a linguistic failure of the Swedish company.

The second category, “cultural failures,” usually occur due to a mismatch between the norms, customs and references of the source and target cultures. If humor is about revealing a truth or inoffensively breaching a social norm, what truths can be safely exposed? What are the social norms? What is (in)offensive? The answer to all these questions? Culture. Every culture is idiosyncratic, and so is everything considered funny: Wordplay is sought out in some cultures while it raises eyebrows in others. Some communities enjoy self-deprecating humor, others find it deeply offensive. As Chinese American comedian Joe Wong commented, “in America, it’s funny to poke fun at yourself. But in China, there’s no humor in misfortune.” Assuming intercultural similarity where there is none is almost always an invitation for failure (and sometimes, serious trouble).

Culturally insensitive messages may simply result from an unfortunate lack of consideration for cultures other than that of the creator of the message. For example, a 2011 tweet by American fashion designer Kenneth Cole “humorously” alluding to the uprising in Egypt to promote their spring collection created a backlash that resulted in a major PR crisis. Even though the “joke” was never translated into Arabic, it showcases that any attempt at humor that fails to “read the global room” is deeply detrimental to businesses.

In other cases, a cultural failure comes down to the fact that copywriters and translators are blinded by their own clever jokes and fail to take into consideration the cultural repercussions of their message. This happened, when translators of the video game Cyberpunk 2077 in Turkey replaced part of a motto coined by the nation’s founding leader Atatürk (which became the slogan for the Turkish Air Force) with a rhyming profanity and used it in the localized version of the game, unleashing nationwide uproar amongst gamers (article in Turkish).

Transcreating humor with the target audience in mind

When localizing humor, messages that overlook the sensibilities of the target culture or intricacies of the target language fall flat, or worse, offend the audience. This means, they miss an invaluable opportunity to connect, which in turn can be detrimental to business success. The solution is to transcreate humor, rewriting it from scratch for the target audience. This is something that can be best executed by language-savvy, empathetic and intuitive humans who are immersed in the target culture to a degree that enables them to “read the room” and redesign the message accordingly. The many professionals on Blueprint’s localization team meet this tall order on a day-to-day basis and put their expertise to work in a culture that balances impeccable execution with a healthy level of levity.

Check out what we do to learn more about the wide range of localization expertise Blueprint Technologies offers.